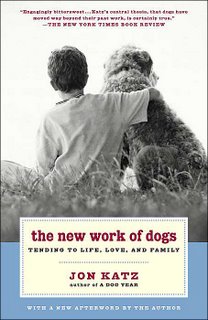

written by Jon Katz

written by Jon KatzOkay, okay, I know I just blogged about another dog book a couple entries ago. I can see all you cat people rolling your eyes and pursing your lips, and I promise that this blog will not become all dogs all the time. But when my librarian sister-in-law Michelle told me about this book I really wanted to investigate. Plus, something silly in me just couldn't resist a dog book written by a person named Katz.

It's a social commentary, not a novel — although some of the characters could easily be something out of strange fiction. Katz gives you a snapshot of several dog owners in and around the spendy suburb of Montclair, New Jersey. His intent is to illustrate anecdotally how we as a culture depend on these "social parasites" (his phrase, not mine) to fill all kinds of emotional and social needs that, once upon a time were fulfilled by other humans. No big surprise there, right? I mean, anyone who's ever loved a dog knows that these animals provide the kind of companionship that truly does earn them the nickname "man's best friend."

Some of the dog owners he shadows are downright pathological. Others are a bit more "normal" but reveal some of the foibles we've all seen in certain dog owners (and maybe in ourselves): for example, the lonely, childless dog owner who treats her canine as a surrogate child. Or the manly-man dog owner who connects easily and naturally with his gargantuan Labrador yet can't connect in a significant way with his wife or kids. Or the tireless dog-rescue lady who spends every spare moment and dime caring for discarded pets and finding them new homes. All of the dog lovers he describes, though, share a common dependence on dogs that begs some hard questions: Are dogs capable of filling the social and emotional expectations we have of them? Are we better off for forcing them into these roles? Are they?

Really cool elements:

- It's an interesting idea, this concept of dogs taking on a "new work" in our culture — where their job is to satisfy humans' social and emotional needs. In a postmodern society that no longer relies so much on family and other human relationships to cement our social network, I can totally see how dogs have found themselves filling an almost-human role. (Heck, look at me! I'm the one who acquired a family dog just weeks before my youngest kid started attending full-day school! Coincidence?)

- In his portrayal of a dog-rescue operation, Katz brings up a good point: howcome there are people out there who will lay down their very lives for dogs — showing mercy and acceptance even for animals who are aggressive and dangerous — yet we have trouble doing the same thing for people?

- Katz sends a message that it's not necessarily healthy to humanize our animals — to attribute all kinds of complex expression and emotion to a dog is to really make the dog into something bigger than life. It's a good reality check to remember that no, they really are animals. Beasts. Nice beasts, sure, but not people.

- Several stories in the book underscore the problem of "throw-away pets"—animals that are abandoned or mistreated because the owners had no idea what they were getting themselves into. I'm all for raising awareness of that problem, in the hopes that it might convince readers to adopt homeless animals rather than add to the problem by purchasing or breeding more dogs.

- Katz believes that dogs really are not the fiercely loyal, undyingly loving creatures that many of us dog people make them out to be. In fact, he suggests that if your dog is separated from you for a couple weeks and is given a comfortable place to live and lots of food, he'll promptly forget you ever existed. I'm sorry, but Buster and I both object to that sentiment. :)

- There is an off-color statement near the end of the book that refers to physical training tools (such as choke-chains and invisible fences) as torturous. Katz even implies that those who use such tools are lazy and irresponsible pet owners. Now that felt pretty judgmental! I care for my dog, I walk him several times a day, and I do not take shortcuts in providing care for him. I would even go so far as to say I love my dog. I also know that, because of our proximity to a very busy road, I cannot risk him darting out of the yard after a rabbit or a squirrel. So I use an invisible fence. I won't defend here why I think it's appropriate, but suffice to say that not all pet owners who use them are lazy, irresponsible, or inhumane.